Radford branch

Click on the image to open a pdf of the early tree for this branch.

Press the back button on your web browser

to return to this page.

So far, we have 150 people on this tree.

We have used the following abbreviations on the tree:

b : birth

c : christening or baptism

m : marriage

d : death

bu : burial.

The early family

Photo by Pierre Bamin on Unsplash

The most recent information we have is that the descendants of Joseph and Elizabeth are living in Nottinghamshire, Lincolnshire, the West Midlands and Wales.

Benjamin Fairholm - Indian Mutiny & 2nd Opium War

From the record of the proceedings of a regimental board Dublin 05 April 1862 Discharge no. 645.

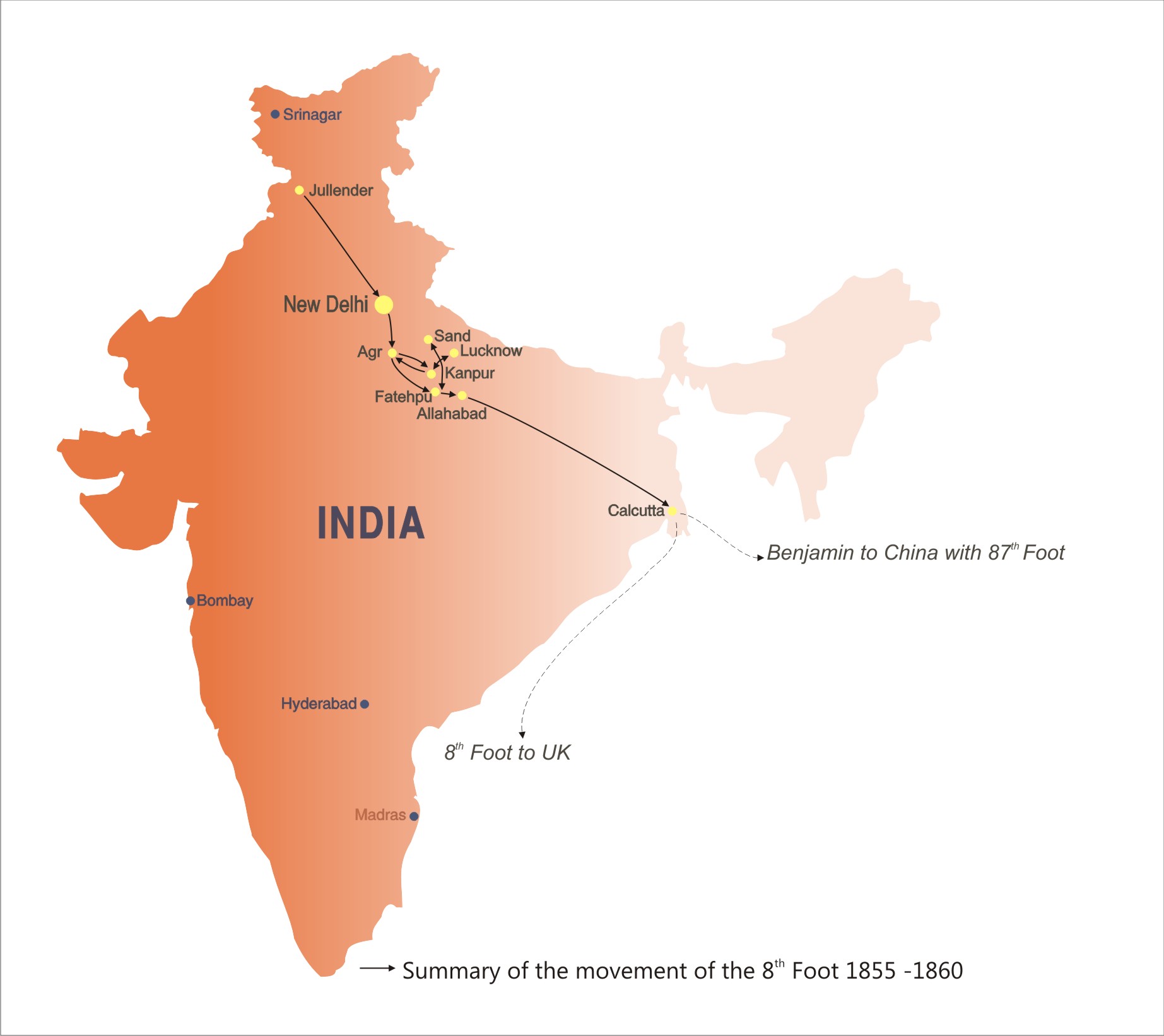

Benjamin Fairholm joined the King’s Regiment (8th Foot) in 1855 and arrived in India in November that year. In 1857 he was involved in the responding to a local outbreak of the Indian Mutiny at Jullender and received the India Mutiny Medal for this. The regiment moved onto help regain Delhi, which had been taken by the mutineers and then proceeded to Agra, clearing up pockets of rebels on the way. In November 1857 the 8th Foot helped to relief the hard pressed garrison at Lucknow and In 1858 formed the garrison at Futtehghur.

In late 1859 and into early 1860 the regiment traveled to Calcutta, some by bullock cart and some by river in two steamers to prepare for embarkation home. Two hundred and sixty-four officers and privates volunteered to joint other corps. Benjamin joined the 87th Foot which was under orders for active service in China. The main hostilities in the Second Opium War between China and several western countries had ended in 1858. The war had been about enforcing the terms of the treaty that had ended the first war to China's significant disadvantage. However, the Chinese government stalled in complying with the new treaty that had been signed in 1858 and further military action was undertaken by western countries.

Benjamin’s new regiment traveled to Hong Kong on five steam ships. A journey that took five weeks. Instead of proceeding north with the main force the 87th Foot became the garrison for Canton (the main port for trade with the west) and remained there throughout the Summer and Autumn of 1860. Although not involved in any military action, 3 officers and 47 men died during the posting. The Anglo-French force that moved north destroyed palaces belonging to the Chinese Emperor's at Chengde, and Peking, bringing a final end to the war.

The regiment left for home in December 1860, arriving back six months later. They were posted to Dublin and the Curragh Camp.

Having survived three long sea voyages and much fighting, Benjamin contracted chronic bronchitis. His after his arrival home and was discharged from the army as unfit. He returned to Nottingham, but by 1871 was in the Lenton Pauper Lunatic Asylum. He died there in 1874 of consumption aged 37 or 38.

Framework knitting & the textile industry

The textile industry in Nottingham started to use machines as early as 1641. Stockings were being produced on 400 frames by 1700. Much of the production was made of silk, but as the quality of cotton improved there was a switch and cotton became the main material used for knitting in Nottinghamshire. There were eight cotton mills in Nottingham alone by 1794.

Wider frames were developed capable of producing larger pieces of knitted material. This material was then cut up to make clothes which the narrow stocking frames could not handle. Stockings could also be made much cheaper this way too.

The effect of the continuing development of mechanisation, the increased use of the wider frames in knitting, changes in the economy and in fashion resulted in protests from hand loom weavers and makers of fully fashioned stockings who feared for their livelihood. Many frames were destroyed in the Luddite riots which in Nottingham mainly occurred in 1811 and 1812, but lasted intermittently to 1816. Thousands of soldiers were brought in to contain the rioting, but was not succesful because several hundred frames were destroyed. The situation in the country as a whole was such that the Destruction of Stocking Frames, etc. Act 1812 was passed making destruction of a frame punishable by death. Several MPs from Nottinghamshire promoted the bill through parliament. The penalty was later changed in 1814 to a maximmum of lifetime transporation, but reverted to death in 1817.

Framework knitting could be carried out in the home because the frames were powered physically. It was a family activity: the husband operated the frame, his wife seamed the stockings and, with any children, transferred the yarn from hanks to bobbins.

Most knitters rented their frames from master hosiers or intermediaries, who generally also allocated work and supplied the yarn. In 1844 the rent for a narrow frame was around 1 shilling a week and for a wide one up to 3 shillings. Payment for the finished items was on a piece rate.

In 1844 a government commission investigated the textile industry after a petition from 25,000 framework knitters. Unfortunately, nothing beneficial came of it. However, the evidence collected indicates the level of poverty in which many knitters lived. One third to one half of their income was spent on work expenses of one sort or another. After paying their work expenses and rent some families of two adults and four children were left with as little as 3 shillings and 6 pence to live on for a week. A loaf of bread cost 6 pence. Many had to pawn their clothes on a regular basis to buy food.

Some houses were especially built to accommodate the frames, but many frames were in ordinary houses and conditions were cramped. A particular feature of a framework knitter’s house was wide windows to make maximum use of natural daylight and limit the expense of candles. Workshops, housing several frames, were also built, but it was only after steam power was introduced from the late 1870s that factories were developed. The new powered machines required less physical strength and the industry became increasingly dominated by female labour.

Further development of the frames allowed machine lace to be produced. Lace production expanded rapidly from the 1880s and by 1890 there were 500 hundred lace factories in Nottingham employing over 17,000 workers.

Radford

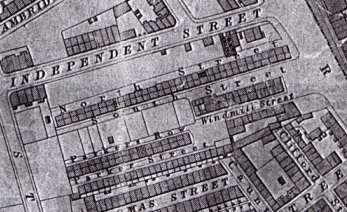

Part of the Sanderson

Map of 1835 reproduced from a

copy held by Nottinghamshire City Library

copy held by Nottinghamshire City Library

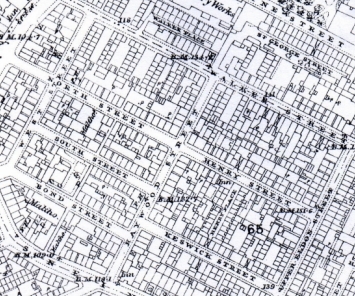

Part

of the map of the town of Nottingham and its

Environs produced for the Duke of Newcastle in 1861 produced from a copy held by Nottinghamshire City Library

Environs produced for the Duke of Newcastle in 1861 produced from a copy held by Nottinghamshire City Library

The second map (from 1861) shows the streets in the area in which the family lived or worked from the early 1800s to at least 1936. The area was called Bottom Buildings. North Street and South Street were later renamed Lea Street and Brassey Street. The properties between North Street and South Street and Parker's Row and Parker Street were back-to-back houses - meaning that only one wall of the house could have windows and doors. Additional terraced properties were built later between South Street and Parker Row (which was made an extension to Windmill Street).

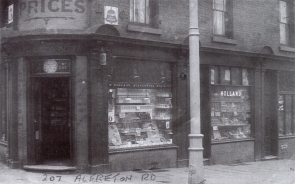

The first old photograph was taken around 1912 and shows the south side of Parker Street just past its junction with Hornbuckle Street. Joseph and Emma Fairholm (nee Cully) lived on this street from at least 1868 to at least 1871. The properties are probably typical of the ones that family members had lived in from the early 1800s in this area. The second old photograph shows the chemists at the junction of Alfreton Road & Independent Street - the street immediately north of where family members lived - circa 1904.

By the start of World War I the area had become run down. Although improvements were made to some of the properties around that time, the streets that the families had lived in had been demolished by the start of World War II and in the 1960s a massive redevelopment took place in this part of New Radford. The modern photograph shows how the area was redeveloped in the 1960s as part of a large scale scheme. It was taken in January 2003.

Reproduced courtesy of

Nottingham City Council Local Studies Library /

www.picturethepast.org.uk.

Picture the Past provides access to a large collection of photographs of Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire for viewing on-line and for purchase. |

Reproduced

with permission of Reflections of a Bygone Age

rom their book Radford with Hyson Green and The Forest on old picture postcards (ISBN 0 946245 83 5) - one of the books in their 'Yesterday's Nottinghamshire' series. |

|

Sneinton

Reproduced from a copy held by Nottingham

City Library

The map from 1881 shows some of the streets where members of the Radford branch and the Southwell 2 branch lived in the the mid to late 1880s : West Street, North Street and Walker Street. The old photograph shows Carlton Road circa 1917 on a postcard published by W. H. Smith. The streets where family members lived were just to the right of the two boys.

Piecemeal redevelopment took place under clearance schemes in the 1930s and a larger scheme took place later. The modern photograph shows the redevelopment of West Street and North Street. It was taken in January 2003.

Reproduced

with permission of Reflections of a Bygone Age from their book

Sneinton and St. Ann's with Carlton Road on old picture postcards (ISBN 0 900138 18 2) - one of the books in their 'Yesterday's Nottinghamshire' series. |

|